Soil Health and the Role of Biostimulants

Informes técnicos

Soil Health and the Role of Biostimulants

Healthy soil is the foundation of sustainable crop production. Yet across many farming systems, soil health is declining due to intensive cultivation, compaction, erosion, and a long-term reliance on synthetic fertilisers. To compensate for nutrient losses, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus, growers are often advised to apply more fertiliser than their crops require. These excess nutrients accumulate in soils before leaching or running off into waterways, contributing to pollution of streams, rivers and lakes (Vance, 2001). Over time, reliance on high fertiliser inputs has created a cycle of diminishing soil function, declining biodiversity, and rising production costs.

The Link Between Fertiliser Use and Soil Biodiversity Decline

Soil biodiversity refers to the immense variety of life within the soil: bacteria, fungi, protozoa, nematodes, earthworms, insects and more. This living community, collectively known as the soil microbiome, plays a central role in nutrient cycling, soil structure and plant health. However, research consistently shows that excessive fertiliser use disrupts this delicate ecosystem. Long-term nitrogen applications reduce microbial biomass and alter community structure (Geisseler & Scow, 2014), while soil acidification caused by nitrogen fertilisers suppresses beneficial microorganisms, including nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Mäder et al. (2002) further demonstrated that organic and low-input systems maintain significantly higher biodiversity and better soil structure than conventional systems relying heavily on synthetics.

Another unintended consequence of fertiliser overuse is reduced organic matter. When crops become reliant on readily available nutrients, they allocate less energy to root development, resulting in lower organic matter inputs into the soil. This deprives microbes of their food source and gradually diminishes both microbial abundance and diversity.

Why Soil Health Matters

Healthy soils are resilient soils. Diverse microbial communities support key ecosystem functions such as nutrient cycling, disease suppression, soil aggregation and carbon storage. When biodiversity declines, soils become more vulnerable to drought, compaction, erosion, waterlogging and disease pressure. Hartmann et al.(2015) highlight that a reduction in microbial diversity reduces functional gene abundance essential for ecosystem services. As climate change increases the frequency of extreme weather events, building biologically robust soils becomes essential for crop productivity and food security.

How Biostimulants and Biofertilisers Support Soil Health

Biostimulants offer growers practical tools to rebuild soil health while reducing reliance on synthetic fertilisers. These products work by stimulating natural soil processes, improving nutrient use efficiency, and enhancing plant resilience. Different categories include:

- Humic and fulvic acids – Improve nutrient availability, buffering capacity and soil structure.

- Seaweed-based biostimulants – Enhance root growth, stress resistance and microbial activity.

- Beneficial bacteria – Support nutrient cycling, nitrogen fixation and organic matter breakdown.

- Beneficial fungi (e.g., mycorrhizae) – Increase root surface area and improve water and nutrient uptake.

- Complex biostimulants – particularly those containing bioflavonoids and polyphenols actively encourage microbiome activity while improving crop yield drought and disease resistance.

Phosphate fertiliser can suffer up to 80% loss if rainfall follows immediately after application due to runoff. Biofilm production from diverse soil microbiome can mitigate this. Complex biostimulants can enhance the microbe population increasing phosphate availability and retention, keeping more nutrients in the root zone where crops can access them.

Practical Solutions for Healthier Soils

Complex biostimulants such as Maxstim’s formulations are designed to support both plant and soil health. Their complex nature gives rise to synergistic effects between the natural plant extracts, bioflavonoids and organic acids stimulates root development and enhances microbial activity in the rhizosphere. This leads to improved nutrient uptake, greater nutrient use efficiency, and reduced dependency on synthetic fertilisers.

Complex biostimulants can also improve nutrient assimilation (e.g. nitrate, ammonium, phosphate, sulphate) by stimulating the gene expression of enzymes involved in plant metabolism or simply as an indirect effect of the increased nutrient uptake and transport.

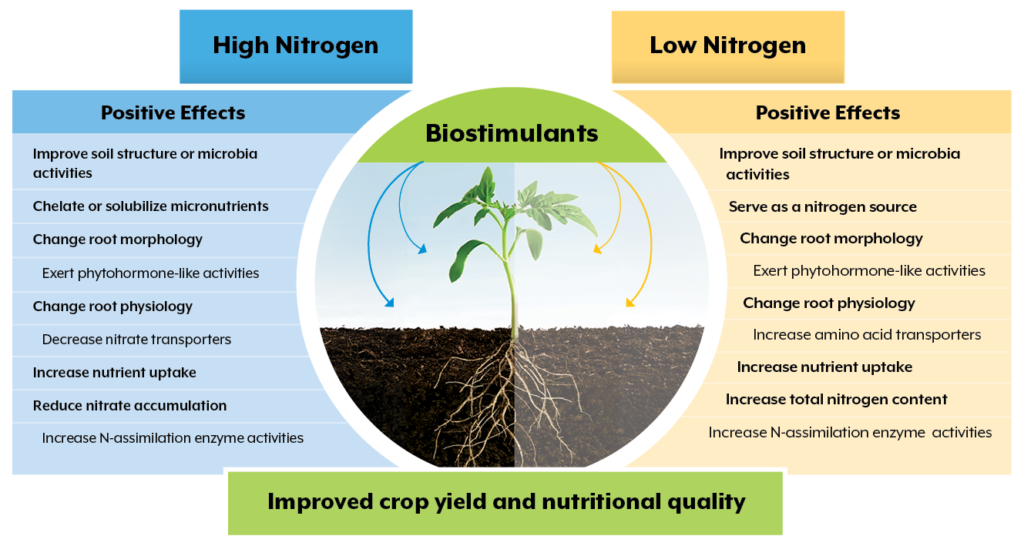

Many of these effects can vary depending on soil nutrient levels and availability. For example, while biostimulants can safeguard crops from low nitrogen by improving crop yield and quality, they may also protect crops from high nitrogen by reducing nitrate accumulation.

Benefits of biostimulants on crop yield and nutrition (Choi and Kim, 2020)

Growers using complex biostimulants such as Maxstim Agriculture+ and Cynosa have reported stronger, deeper root systems and improved soil structure, both essential for reducing compaction, managing waterlogging, and resisting erosion. Enhanced microbial activity also accelerates nutrient cycling, helping crops access phosphorus, nitrogen and micronutrients more effectively.

A Path Toward Sustainable Productivity

As global food demand increases, agriculture must find ways to boost production without further degrading the soil. Biostimulants and biofertilisers provide an effective way forward by working with natural processes instead of against them. By incorporating complex products like Maxstim into their programs, growers can reduce fertiliser inputs, improve soil biodiversity, and build resilient, productive soils for the long term.

References:

Choi, H. and kim, H. J. (2020). Biostimulants as a Safeguard Plants Against Poor Nitrogen Supply. Dept of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, Purdue University, USA.

Geisseler, D., & Scow, K. M. (2014). Long-term effects of mineral fertilizers on soil microorganisms – A review. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 75, 54–63. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.03.023

Hartmann, M., Frey, B., Mayer, J., Mäder, P., & Widmer, F. (2015). Distinct soil microbial diversity under long-term organic and conventional farming. The ISME Journal, 9(5), 1177–1194. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2014.210

Mäder, P., Fliessbach, A., Dubois, D., Gunst, L., Fried, P., & Niggli, U. (2002). Soil Fertility and Biodiversity in Organic Farming Science. Science (New York, N.Y.), 296, 1694–1697. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1071148

Vance, C. P. (2001). Symbiotic nitrogen fixation and phosphorus acquisition. Plant nutrition in a world of declining renewable resources. Plant Physiology, 127(2), 390–397.